Previous: Trivia Notebook #3

Welcome back for some more trivia! Again, thanks to all those who have suggested topics. Feel free to drop them in the comments here, on Twitter, etc.

Today we’re going to look at Daniil Medvedev’s high ranking sans finals, revisit what would make a good year-end showing for Joao Fonseca, and see who has beaten multiple number ones (past, present, or future) in the same tournament.

Daniil’s Drought

Daniil Medvedev hasn’t won a title since 2023; he hasn’t reached a final since Indian Wells in 2024. He won plenty of matches last year–Wimbledon semi, US Open quarter–so when he lost at Indian Wells last month, he was still ranked sixth in the world. He has now fallen out of the top ten, but for a fortnight, he was a top-tenner without a single final in the previous 52 weeks.

That is unusual:

Since 1982, the beginning of my reliable week-by-week ATP rankings data, only a few dozen players have held a place in the top 30 without the points from a single final.

Only nine have clung to a spot in the top 20. (I’m not counting Roger Federer, who remained in the top ten after the Covid-19 pause and held on to a top 20 place for a long time because of the pandemic adjustments to the ranking rules.)

Medvedev is not the first top-tenner, but his ranking in Miami is the “best” of all-time:

Rank Player Date 8 Daniil Medvedev 20250317 10 Fernando Gonzalez 20100301 19 Goran Ivanisevic 20020701 19 Lucas Pouille 20191014 20 John McEnroe 19921026 20 Gaston Gaudio 20060731 20 Andrei Medvedev 20000529 20 Petr Korda 19990125 20 Mardy Fish 20120813

(Each player is listed only once, with their best ranking. Most of them spent multiple weeks in the top 20 without the points from a final.)

Gonzo had seven semi-finals to his credit, including Rome and Roland Garros. His final-less ranking position is the only one that comes close to what Medvedev has (not) achieved lately.

Fonseca’s company

In the first Trivia Notebook, I looked at big ranking leaps into the top 100. The goal was to find some context for Joao Fonseca, who started the year at #145 and had already reached an Elo rating in the top 50. Sure enough, his position on the official table has quickly followed. He’s up to 59th, and he doesn’t have many points to defend for the rest of the year.

And he’s up to 11th on my Elo list. That’s not a guarantee he’ll climb so high on the ATP table, but it suggests he won’t be 59th for long.

A one-hundred point leap into the top 50, as it turned out, wouldn’t be all that historic. Eric J followed up to ask:

How high would he have to get from his starting position for it to be a historically interesting result?

Let’s say that the reference class for Fonseca consists of players who finished a year ranked between 120 and 180. Again going back to the early 80s, here are the players from that group who reached the best rankings in the following year:

Player Year YE-Rk Next YE Gain Goran Ivanisevic 2000 129 12 117 Mikael Pernfors 1985 165 12 153 Andy Roddick 2000 156 14 142 Paradorn Srichaphan 2001 120 16 104 Fernando Gonzalez 2001 139 18 121 Henrik Holm 1991 131 19 112 Nicolas Jarry 2022 152 19 133 Jan Lennard Struff 2022 150 25 125 Jan Siemerink 1990 135 26 109 Milan Srejber 1985 121 27 94 Claudio Mezzadri 1986 138 28 110 Bohdan Ulihrach 1994 142 28 114 Dmitry Tursunov 2012 122 29 93 Francisco Cerundolo 2021 127 30 97 Tommy Robredo 2000 131 30 101 Michael Chang 1987 163 30 133

(“Year” refers to the season with the ranking between 120 and 180: The breakthrough came the following season.)

No one has ever gone from a ranking in this range to the top ten. Fonseca has a chance to be the first.

Perhaps more to the point is how the Brazilian would stack up against other teens. Most of the players on that list are young, but the whole notion of “ranking leaps” can distract us from what really matters.

Fonseca will be 19 at the end of the year. Here are the last ten teenagers to finish a season in the top 20:

Player Year YE Rank Carlos Alcaraz 2022 1 Holger Rune 2022 11 Novak Djokovic 2006 16 Andy Murray 2006 17 Rafael Nadal 2005 2 Richard Gasquet 2005 16 Andy Roddick 2001 14 Lleyton Hewitt 2000 7 Andrei Medvedev 1993 6

Pretty good company. Again, there’s a lot to do in the next seven months or so. Elo is a good forecasting tool, but the exact timeline is much tougher to get right. If Fonseca does live up to expectations on schedule, he’ll be in elite company.

Defeats of past and future

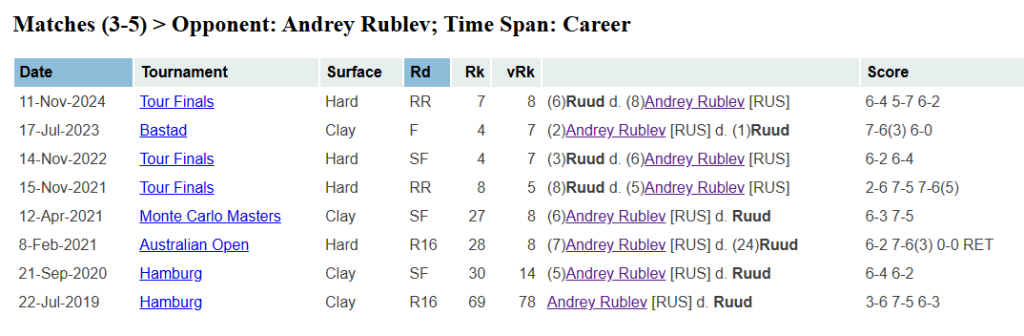

In the February roundup, I linked to full match video of Andy Murray’s 2005 US Open match against Arnaud Clement. Edo took the cue and charted the match (he’s now past the 1,700 mark!), and he observed that in the same tournament, Clement beat Murray–then a future number one–and former top dog Juan Carlos Ferrero.

Pretty good run for the 91st-ranked Frenchman, especially in retrospect. Alas, he lost to Nicolas Kiefer in the third round.

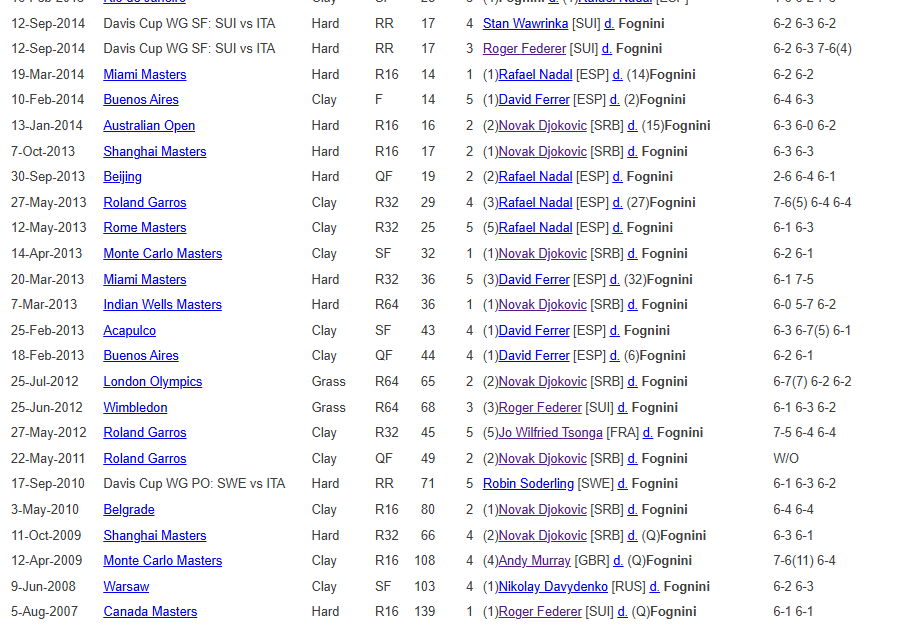

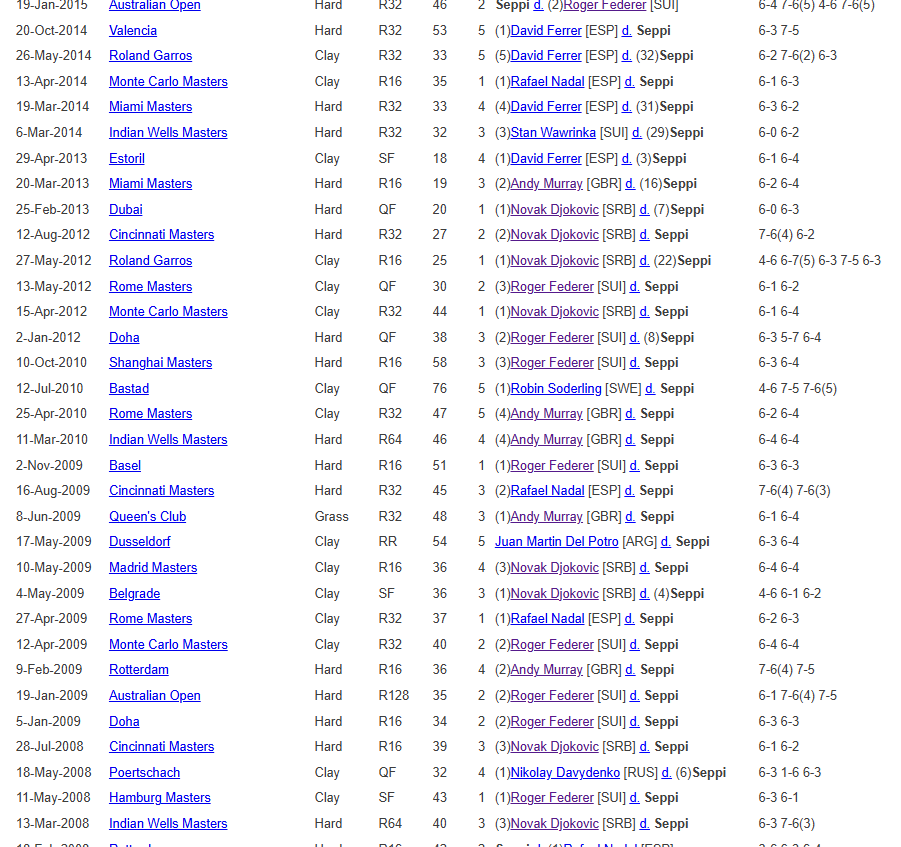

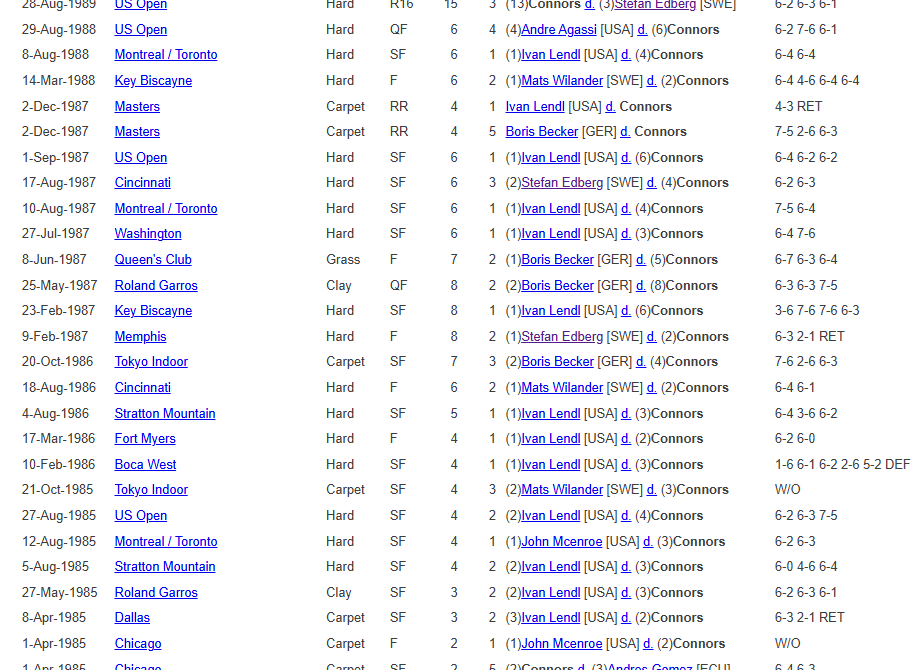

It turns out that a lot of players have beaten multiple (past, present, or future) number ones in the same tournaments. It’s especially common in eras where several men have cycled through the number one position: Not only are number ones comparably weaker, there are more opportunities.

Let’s strengthen the parameters to make it more interesting. How many players have done the same as Clement, beating a former number one and a present or future number one at the same event, while ranked outside the top 50 himself?

Clement is one of 25 men to accomplish the feat. But the Frenchman is an even more unique case. He is one of just two players–Slava Dosedel is the other–to have done it twice! A year after his US Open run, he beat Lleyton Hewitt, Marat Safin, and Murray again (also charted by Edo) to win the Washington title.

Dosedel is the only man to have done this on multiple surfaces. He won the 1996 Munich title with wins over Boris Becker and Carlos Moya on clay. Then he defeated Jim Courier and Pat Rafter at the 1999 Adelaide event, before–get this–losing to Hewitt.

Clement and Dosedel both came along in the right era for this: 24 of the 27 instances took place between 1995 and 2006. The only example since 2006: the 2018 Australian Open, when Hyeon Chung knocked out both Novak Djokovic and Daniil Medvedev.

Most impressive of all is a run you’ve surely heard about before. Goran Ivanisevic claimed the 2001 Wimbledon title as a wild card, with wins against former number ones Moya, Rafter, and Safin, plus a victory over future number one Andy Roddick. That single tournament–not to mention Goran himself–continues to be the trivia answer that keeps giving.

See you next time!

* * *

Subscribe to the blog to receive each new post by email: