Italian translation at settesei.it

Last week’s Olympic tennis tournament had superstars, it had drama, and it had tears, but it didn’t have ranking points. Surprise medalists Monica Puig and Juan Martin del Potro scored huge triumphs for themselves and their countries, yet they still languish at 35th and 141st in their respective tour’s rankings.

The official ATP and WTA rankings have always represented a collection of compromises, as they try to accomplish dual goals of rewarding certain behaviors (like showing up for high-profile events) and identifying the best players for entry in upcoming tournaments. Stripping the Olympics of ranking points altogether was an even weirder compromise than usual. Four years ago in London, some points were awarded and almost all the top players on both tours showed up, even though many of them could’ve won more points playing elsewhere.

For most players, the chance at Olympic gold was enough. The level of competition was quite high, so while the ATP and WTA tours treat the tournament in Rio as a mere exhibition, those of us who want to measure player ability and make forecasts must factor Olympics results into our calculations.

Elo, a rating system originally designed for chess that I’ve been using for tennis for the past year, is an excellent tool to use to integrate Rio results with the rest of this season’s wins and losses. Broadly speaking, it awards points to match winners and subtracts points from losers. Beating a top player is worth many more points than beating a lower-rated one. There is no penalty for not playing–for example, Stan Wawrinka‘s and Simona Halep‘s ratings are unchanged from a week ago.

Unlike the ATP and WTA ranking systems, which award points based on the level of tournament and round, Elo is context-neutral. Del Potro’s Elo rating improved quite a bit thanks to his first-round upset of Novak Djokovic–the same amount it would have increased if he had beaten Djokovic in, say, the Toronto final.

Many fans object to this, on the reasonable assumption that context matters. It certainly seems like the Wimbledon final should count for more than, say, a Monte Carlo quarterfinal, even if the same player defeats the same opponent in both matches.

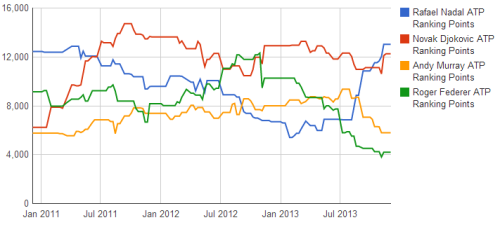

However, results matter for ranking systems, too. A good rating system will do two things: predict winners correctly more often than other systems, and give more accurate degrees of confidence for those predictions. (For example, in a sample of 100 matches in which the system gives one player a 70% chance of winning, the favorite should win 70 times.) Elo, with its ignorance of context, predicts more winners and gives more accurate forecast certainties than any other system I’m aware of.

For one thing, it wipes the floor with the official rankings. While it’s possible that tweaking Elo with context-aware details would better the results even more, the improvement would likely be minor compared to the massive difference between Elo’s accuracy and that of the ATP and WTA algorithms.

Relying on a context-neutral system is perfect for tennis. Instead of altering the ranking system with every change in tournament format, we can always rate players the same way, using only their wins, losses, and opponents. In the case of the Olympics, it doesn’t matter which players participate, or what anyone thinks about the overall level of play. If you defeat a trio of top players, as Puig did, your rating skyrockets. Simple as that.

Two weeks ago, Puig was ranked 49th among WTA players by Elo–several places lower than her WTA ranking of 37. After beating Garbine Muguruza, Petra Kvitova, and Angelique Kerber, her Elo ranking jumped to 22nd. While it’s tough, intuitively, to know just how much weight to assign to such an outlier of a result, her Elo rating just outside the top 20 seems much more plausible than Puig’s effectively unchanged WTA ranking in the mid-30s.

Del Potro is another interesting test case, as his injury-riddled career presents difficulties for any rating system. According to the ATP algorithm, he is still outside the top 100 in the world–a common predicament for once-elite players who don’t immediately return to winning ways.

Elo has the opposite problem with players who miss a lot of time due to injury. When a player doesn’t compete, Elo assumes his level doesn’t change. That’s clearly wrong, and it has cast a lot of doubt over del Potro’s place in the Elo rankings this season. The more matches he plays, the more his rating will reflect his current ability, but his #10 position in the pre-Olympics Elo rankings seemed overly influenced by his former greatness.

(A more sophisticated Elo-based system, Glicko, was created in part to improve ratings for competitors with few recent results. I’ve tinkered with Glicko quite a bit in hopes of more accurately measuring the current levels of players like Delpo, but so far, the system as a whole hasn’t come close to matching Elo’s accuracy while also addressing the problem of long layoffs. For what it’s worth, Glicko ranked del Potro around #16 before the Olympics.)

Del Potro’s success in Rio boosted him three places in the Elo rankings, up to #7. While that still owes something to the lingering influence of his pre-injury results, it’s the first time his post-injury Elo rating comes close to passing the smell test.

You can see the full current lists elsewhere on the site: here are ATP Elo ratings and WTA Elo ratings.

Any rating system is only as good as the assumptions and data that go into it. The official ATP and WTA ranking systems have long suffered from improvised assumptions and conflicting goals. When an important event like the Olympics is excluded altogether, the data is incomplete as well. Now as much as ever, Elo shines as an alternative method. In addition to a more predictive algorithm, Elo can give Rio results the weight they deserve.