Italian translation at settesei.it

21st-century women’s tennis is a baseline game. Some players are better able to identify opportunities to approach the net than others, and some can handle themselves quite well when they get there. But if a fan from a few decades ago were dropped off at the 2014 Australian Open, she would be shocked by the rarity of net points and the clumsiness of many players when they move forward.

Since almost all television commentators were excellent players in a more net-centric era, a frequent refrain during almost any broadcast is that players should rush the net more often. “Frequent” might be understating it–in a fit of pique, I was driven to say this:

Regardless of repetition, it’s worth further investigation. It’s certainly true that a skilled netwoman could win more points by moving forward. But when pros don’t emphasize that part of their game and they gain little match experience approaching the net, do they have the skills necessary to take advantage of such an opportunity?

Enter some numbers

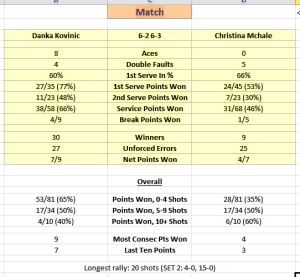

At this point, you might be tempted to look at the oft-collected “Net Points” stat. Resist the urge. In a baseline-oriented match, net points can have little to do with net approaches. Attempting to return a drop shot is considered a net point. Putting away a weak service return is considered a net point. In many WTA matches, more than half of “net points” do not involve an approach. The player was induced to come to the net for some reason.

Making matters worse, that non-approach segment of net points has little to do with net approaches. Given a weak, floating return, any competent player should be able to whack it for a swinging volley winner. At the other end of the spectrum, chasing down a drop shot relies on a different set of skills than picking a moment to hit an approach shot and then confidently placing a volley or two.

Fortunately, the Match Charting Project gives us some more detailed, approach-specific data.

Twenty matches in the charting database are from the first month of the 2014 WTA season, most of them from the first week in Melbourne. This data differentiates between “net approaches” and “net points.” In one of the more aggressive performances in the database, Angelique Kerber, in her loss to Tsvetana Pironkova in Sydney, won 15 of 19 net points. Of her ten net approaches, she won all ten.

(For any match report in the charting database–here’s the Kerber-Pironkova match–click one of the two “Net Points” links to see those stats. There is a different table for each player.)

Kerber’s ten net approaches is tied for the most of any of the WTA matches that have been charted this year. Last night, Garbine Muguruza also tallied ten net approaches, though she did so in a longer match.

In these twenty matches, only 27 of 40 players made even one traditional net approach. Including those who made zero, the average is just over three net approaches per match. The 27 who approached the net at least once averaged 4.7 per match.

Clearly, a lot of opportunities for offense are going unclaimed.

How they’re doing

Of the 126 net approaches we’ve tracked, the approaching player has won 84–exactly two-thirds. While that isn’t an overwhelming endorsement–many approach shots are hit in response to a weak groundstroke that already puts the opponent at a disadvantage–it certainly doesn’t count as evidence against the practice.

In half of all net approaches, the netrusher either hits an outright winner at the net or induces a forced error with a net shot. Only 12% of the time does the opponent hit a passing shot winner. In another 5% of these points, the opponent induces a forced error with a passing shot. In 12% of net approach points, the player who moved forward hits an unforced error at the net.

Of the 27 players in the database who approached the net at least once, only six failed to win half of those points (three of whom only came forward once), and three more won exactly half of their net approach points.

The women in this sample who seize the most opportunities to rush the net have been particularly successful, as well. Seven of the eight who moved forward the most won more than half of their approach points. This allows us to tentatively conclude that all the other players–the ones who picked only a few spots to approach the net during their matches–could have seized more opportunities. There may be a limit in the modern game to how much netrushing is wise, but the observed maximum of ten points per match doesn’t seem to be it.

Inevitable unknowns

Whether we look at Kerber and her 10/10 net-approach performance in Sydney or Sloane Stephens and her 1/1 tally yesterday against Elina Svitolina, it’s impossible to know the results of the next approach shot–or the next five. We can compare single-match results and see that it’s possible for a WTA player to have a perfect record on her ten net approaches, but we can’t perform lab experiments in which Sloane plays Svitolina again and comes forward ten times instead of one.

For all the success that players enjoy when they do move forward, there are plenty of reasons not to. As I said at the outset, today’s players don’t practice net skills nearly as much as baseline skills, and they certainly don’t get much in-match practice. If someone isn’t comfortable approaching the net at a certain time, is it really a good idea for her to do so?

In the abstract, both intuition and statistical analysis supports the position that WTA players could move forward more. When they do approach the net, they are often successful, putting away volley winners and rarely getting passed. But I suspect this implies a long-term strategy more than the sort of thing a coach should emphasize during a changeover.

When commentators suggest that a player should move forward, what I think they really mean is this: “If this player were more comfortable with her transition game, this would be a great opportunity to take advantage of that.” Or: “Players should work harder on their approach shots on the practice court so that they’re ready for opportunities like this one.” Or simply: “Martina would have won that point ten shots ago.”

There seems to be opportunity waiting for more, well, opportunistic young players. But it isn’t one that can be generated simply by a sudden coaching change or a harangue from John McEnroe. Only when a player emerges with the baseline game to contend with the best pros and a transition/net game that exceeds most of those on the tour today will we find out just how much opportunity today’s players have wasted.